Almost 100% of the forest in Sabah was already logged, there was hardly any primary forest, so the government there was very worried about the orangutans and whether or not they would survive, but in fact up until then there hadn’t been any studies on how orangutans adapt to secondary forest.Įven so, when I went to Kinabatangan that very first time, I could see quite a lot of orangutan nests. Most importantly, all the orangutan experts working in Indonesia at that time were saying that orangutans cannot survive in degraded secondary forest, that if the forests were logged then you lost the orangutans and all of the forest. At that time, everybody told me that there were plenty of orangutans in Borneo, but they didn’t know where and they didn’t know how many. At first I was looking for a job there, but I couldn’t find anything, so in the end I decided to start my own project. I first went to Borneo in 1994 to meet with local conservation NGOs and local government to find out what was needed most. I wanted to do a PhD but couldn’t find a project that would take me, or that had funding, so I ended up studying baboons in Saudi Arabia – which was extraordinary – but after a few years there I still had that desire to study orangutans. This interest eventually led to me working with and studying orangutans in zoos in various countries. But I was able to take care of them, and began to learn and read more about orangutans and wild orangutans – so I guess that’s how it started originally.

This gave me an opportunity to study them, although there was really nothing to study, they were just two terrified baby orangutans. When I was studying Biology at university in Paris, two orphan orangutans were seized at the airport and taken to the zoo right next to my university.

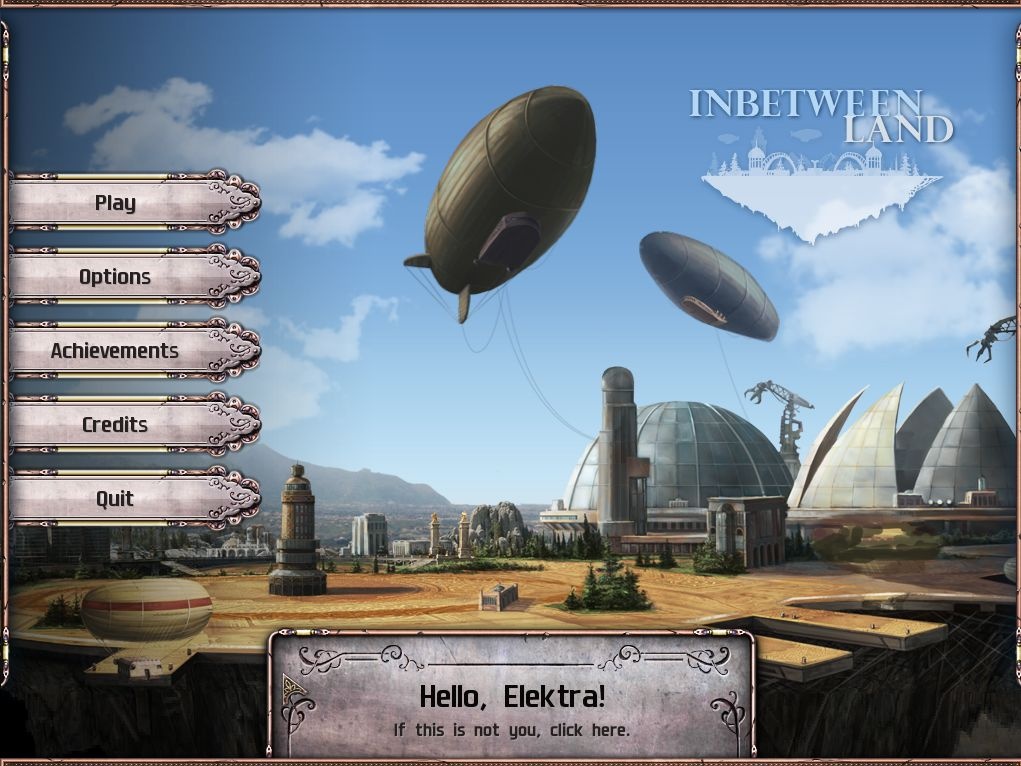

I wanted to study them and become a wildlife researcher, specifically to research primates. Could this be you? This an excerpt of a Resonate article.An Early Passion Q: What first drew you into conservation when you were growing up?Īctually, when I was growing up I was always interested in wild animals. Suzanne is seeking individuals and churches to partner with her prayerfully and financially. Preparing is a whirlwind, but so is intercultural work! Above all else, I feel thankful that it’s a journey we never have to walk alone, but hand-in-hand with the God who calls us." My timing is not the same as God’s and He is under no obligation to keep to my schedule! It’s in the inbetween that I’m learning patience when I’m itching to finally join the team. Inbetween places: Boxing and donating the parts of my house I won’t bring with me, while checking Silk Road weather forecasts and imagining cycling to the bazaar. Inbetween communities: Finding ways to cherish and value the time I have left face-to-face with loved ones before I go, while building friendships and getting to know new team members and people from my future host community. Inbetween jobs and roles: Balancing the responsibilities of finishing my work as a teacher in Australia well, while starting to transition into a host of new opportunities, tasks and things to learn on the Silk Road.

When you’re preparing, you live in the land of inbetweens. Each of those 12 years have been part of the preparation that eventually led me to Baptist Mission Australia and the Silk Road Area.

If He told me what He wanted me to do with it, I would do it – no asterisk, no take-backs. I’m 28 now. On a Christian camp, I prayed a scary prayer. I heard the call to mission when I was 16. "Preparing for intercultural work is many things but very rarely boring! In a way, I’ve been doing it for the last 12 years, and yet new emotions, experiences and questions always find a way to appear. Here she explores what it feels like to live in the inbetween world of preparation. Suzanne is getting ready to serve in the Silk Road Area. What does it feel like to prepare for intercultural work?

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)